The Silent Parade & the 1917 St. Louis Race Riot

- Sep 1, 2014

- 7 min read

Research by: Masai M. Heard

Family,

After learning how closely connected these two events are, I thought it would be fitting to combine the two in one article. I don't always want the Black History column to focus on the heinous murders perpetrated on Black Americans throughout history (and today, mind you), but this type of article is imperative to pass on to young Black children who, otherwise, aren't taught why carrying themselves in undignified ways is a slap in the face, and to whom.

Otherwise, stories about our forefathers paying dues or about the countless lives that were involuntarily sacrificed are just the rhetoric of the older generation perceived as not hip enough to see how cool saggin' is... or how being a ride-or-die for "the block" is a badge of honor... or how robbing and killing your own or any others is a path to street cred.

They need to know that someone died for them to have the right to disrespect themselves. So... the positive history is coming back soon. For now, please share these stories with the youth around you. If for no other reason than to show that the attitude toward them hasn't really changed. Same lynch, different rope. 1917 was almost 100 years ago, ya know.

-V. Ray

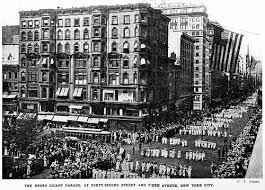

THE SILENT PROTEST PARADE

Harlem, NY July 28, 1927

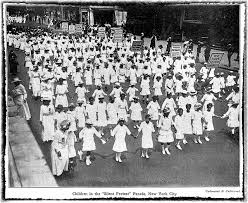

On July 1, 1917, two white policemen were killed in East St. Louis, Illinois, in an altercation caused when marauders attacked black homes. The incident sparked a race riot on July 2, which ended with forty-eight killed, hundreds injured, and thousands of blacks fleeing the city when their homes were burned. The police and state militia did little to prevent the carnage. On July 28, the NAACP protested with a silent march of 10,000 black men, women, and children down New York’s Fifth Avenue. The participants marched behind a row of drummers carrying banners calling for justice and equal rights. The only sound was the beat of muffled drums.

The march was organized by an ad-hoc group formed at St. Philip’s Church in Harlem. James Weldon Johnson was a key organizer of the “Negro Silent Protest Parade.” As the protesters marched silently down 5th Avenue, Boy scouts distributed fliers describing the NAACP’s struggle against segregation, lynching, discrimination, and other forms of racist oppression. It’s hard to imagine Boy and Girl Scouts in the 21st century participating in a mass protest against racialized mass incarceration…

Men, women, and children carried placards that read: “MOTHER, DO LYNCHERS GO TO HEAVEN?; “GIVE ME A CHANCE TO LIVE”; “TREAT US SO THAT WE MAY LOVE OUR COUNTRY”; “MR. PRESIDENT, WHY NOT MAKE AMERICA SAFE FOR DEMOCRACY?; AND “YOUR HANDS ARE FULL OF BLOOD.”

NAACP literature outlined the objectives and goals of the march:

We march because by the Grace of God and the force of truth, the dangerous, hampering walls of prejudice and inhuman injustices must fall.

We march because we want to make impossible a repetition of Waco, Memphis, and East St. Louis, by arousing the conscience of the country and bringing the murderers of our brothers, sisters, and innocent children to justice.

We march because we deem it a crime to be silent in the face of such barbaric acts.

We march because we are thoroughly opposed to Jim-Crow Cars, Segregation, Discrimination, Disfranchisement, Lynching, and the host of evils that are forced on us. It is time that the Spirit of Christ should be manifested in the making and execution of laws.

We march because we want our children to live in a better land and enjoy fairer conditions than have fallen to our lot.

The 1917 St. Louis

RACE RiOT

What is the 1917 St. Louis Race Riot? It's the race riot that occurred in the industrial city of East St. Louis, Illinois, over July 2-3, 1917. It is also referred to as the “East St. Louis Riot.” As historians have looked at its various causes, they have labeled it in different ways, depending on what aspect of it they have focused their attention on. Some recent historians have called it a “pogrom” against African Americans in that civil authorities in the city and the state appear to have been at least complicit in—if not explicitly responsible for—the outbreak of violence. Even in 1917, some commentators already made the comparison between the East St. Louis disturbance and pogroms against Jews that were occurring at the time in Russia.

Roving mobs rampaged through the city for a day and a night, burning the homes and businesses of African Americans, stopping street cars to pull their victims into the street, and assaulting and murdering men, women, and children who they happened to encounter. A memorial petition to the U.S. Congress, sent by a citizen committee from East St. Louis described it as “a very orgy of inhuman butchery during which more than fifty colored men, women and children were beaten with bludgeons, stoned, shot, drowned, hanged or burned to death—all without any effective interference on the part of the police, sheriff or military authorities.” In fact, estimates of the number of people killed ranged from 40 to more than 150. Six thousand people fled from their homes in the city, either out of fear for their lives or because mobs had burned their houses.

The Background

In the early years of the 20th century, many industrial cities in the North and the Midwest became destinations for African Americans migrating from the South, looking for employment. East St. Louis was one of these cities, where blacks found opportunities to work for meatpacking, metalworking and railroad

companies.

The demand for workers in these companies increased dramatically in the run-up to World War I. Some of the workmen left for service in the military, creating a need for replacements, and the demand for war materiel increased industrial orders. The workforce had been highly unionized and a series of labor strikes had increased pressure on companies to find non-unionized workers to do the work. Some companies in East St. Louis actively recruited rural Southern blacks, offering them transportation and jobs, as well as the promise of settling in a community of neighborhoods where African Americans were building new lives strengthened by emerging political and cultural power. By the spring of 1917, about 2,000 African Americans arrived in East St. Louis every week.

The Riot

Racial competition and conflict emerged from this. The established unions in East St. Louis resented the African American workers as “scabs” and strike breakers. On May 28-29, a union meeting whose 3,000 attendees marched on the mayor’s office to make demands about “unfair” competition devolved into a mob that rioted through the streets, destroyed buildings, and assaulted African Americans at random. The Illinois governor sent in the National Guard to stop the riot, but over the next few weeks, black neighborhood associations, fearful of their safety, organized for their own protection and determined that they would fight back if attacked again.

On July 1, white men driving a car through a black neighborhood began shooting into houses, stores, and a church. A group of black men organized themselves to defend against the attackers. As they gathered together, they mistook an approaching car for the same one that had earlier driven through the neighborhood and they shot and killed both men in the car, who were, in fact, police detectives sent to calm the situation.

The shooting of the detectives incensed a growing crowd of white spectators who came the next day to gawk at the car. The crowd grew and turned into a mob that spent the day and the following night on a spree of violence that extended into the black neighborhoods of East St. Louis. Again, the National Guard was sent in, but neither the guardsmen nor police officers were at all effective in protecting the African American residents. They were instead more disposed to construe their job as putting down a black revolt. As a result, some of the white mobs were virtually unrestrained.

The Aftermath

A national outcry immediately arose to oust the East St. Louis police chief and other city officials, who were not just ineffective during the riots, but were suspected of aiding and abetting the rioters, partly out of a preconceived plan, suggested Marcus Garvey, to discourage African American migration to the city.

The recently formed NAACP suddenly grew and mobilized—with a silent march of 10,000 people in New York City to protest the riots. They and others demanded a Congressional investigation into the riots. The report of the investigation, however, pointed to the migration of African Americans to the East St. Louis region as a “cause” of the riot, wording that sounded like blaming the victims. As Marcus Garvey had said of an earlier report of the riot, “An investigation of the affair resulted in the finding that labor agents had induced Negroes to come from the South. I can hardly see the relevance of such a report with the dragging of men from cars and shooting them.”

A similar point about simple justice for the victims and where to place the blame for the riots nearly caused ex-President Theodore Roosevelt to come to blows with AFL leader Samuel Gompers during a public appearance shortly after the riot. Roosevelt demanded that those who had perpetrated the violence and murders in East St. Louis be brought to justice. Gompers then rose to address the crowd and, as a reporter for the Chicago Tribune, wrote, “He read a telegram which he said he had received tonight from the president of the Federation of Labor of Illinois. This message purported to explain the origin of the East St. Louis riots. It asserted that instead of labor unions being responsible for them they resulted from employers enticing Negroes from the south to the city ‘to break the back of labor.’”

This enraged Roosevelt, who jumped up, approached Gompers, brought his hand down onto his shoulder and roared that, “There should be no apology for the infamous brutalities committed on the colored people of East St. Louis.” Roosevelt, like many other Americans of all races, was particularly appalled by the irony that such an event could occur in the United States at the same time that the country, by entering World War I, was declaring its intentions to export abroad its vision of freedom and justice. This theme was picked up by many editorial cartoonists in newspapers across the U.S.

East St. Louis was by no means the only northern industrial city to experience race riots during this period. A conviction grew among some African Americans that they could not depend on an enlightened white community or government, either in the South or in the North, to insure their rights and their safety, but that they would have to fight for their own rights. In an editorial entitled "Let Us Reason Together," in his magazine, The Crisis, W. E. B. Du Bois wrote, “Today we raise the terrible weapon of self-defense. When the murderer comes, he shall no longer strike us in the back. When the armed lynchers gather, we too must gather armed. When the mob moves, we propose to meet it with bricks and clubs and guns.”

Comments